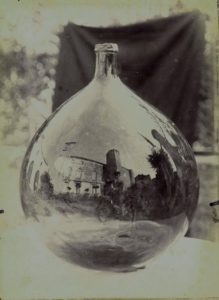

In the heart of France’s Languedoc region, at 10 km from Minerve, the château d’Agel is a superb medieval castle of which the oldest part dates from the 12th century onwards, and consists of the main building, four towers and a dovecote. Its extensive terraced gardens covering 2 hectares (5 acres) offer extensive views over the Cesse valley and the Pech mountain: the ideal setting for a quiet walk or a relaxing dip in the swimming pool.

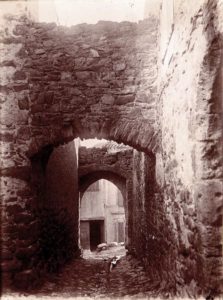

For most of the 12th century, the South-West of what is now France was rocked by the scandal of the Cathar or Albigensian heresy, which challenged the teachings of the church of Rome and thereby the very authority of the Pope, Innocent III. The heresy was strongest in the county of Toulouse and all over Languedoc, where vassals of the Count of Toulouse built a line of fortresses to protect themselves against Vatican agents. After Pierre de Castelnau, despatched by the Pope to restore order in the region, was murdered in 1208, the Pope ordered the northern barons to lead a bloody Crusade against the Cathars.

We know from evidence in the oldest part of the château that in the year 1100 its owner was Bernarde, Lord of Agel, Minerve and Cazelles. The Crusade against the Cathars, led by Simon de Montfort, raged with unremitting violence throughout Languedoc In Simon’s bid to take Minerve in 1210, the château d’Agel was almost entirely destroyed by fire. In July of that year, Minerve finally fell, and the 180 Cathars who had taken refuge there threw themselves on to the burning pyre. The château d’Agel, with its commanding position over the Cesse valley was of great strategic importance to the Cathars. Simon de Montfort ordered Aymeri, viscount of Narbonne, to besiege the château, but Guiraud de Pépieux, Lord of Aigues-Vives and Agel, escaped during the night to Minerve, taking with him two French knights whom he had captured.

It was the Treaty of Paris, which annexed Languedoc to France in 1220, that put an end to the Crusade. Guiraud de Pépieux, who had escaped the massacre, set about restoring the château for his descendants.

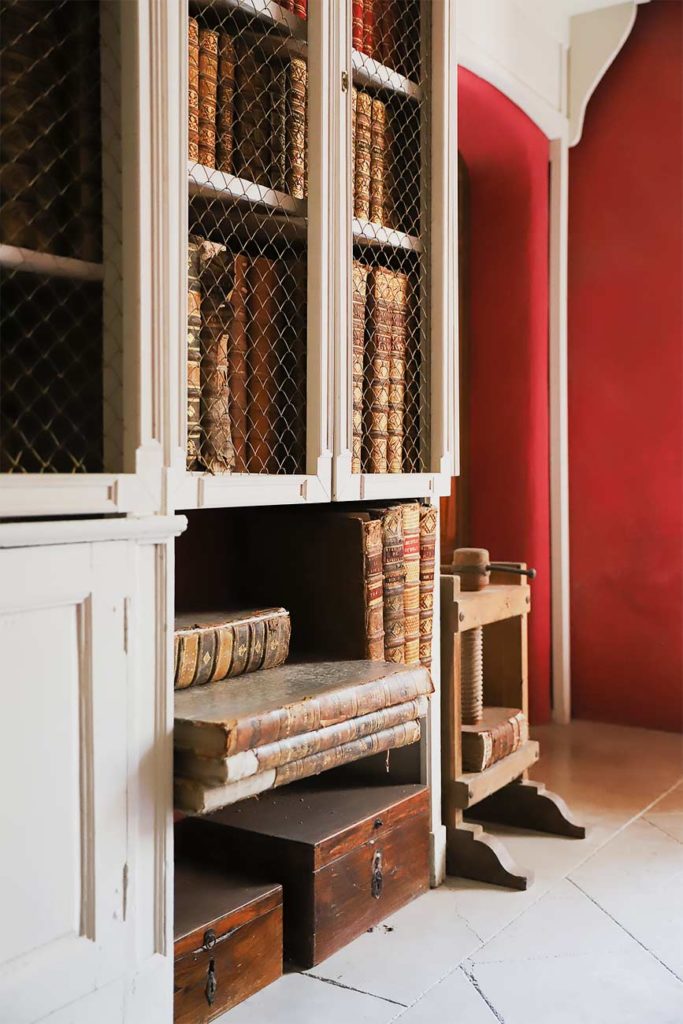

As shown in its variety of window styles, from the tiny windows of the stark 12th century fortress to the beautiful windows of the Renaissance, with their ornamental balusters and chapiters.

During the XVII century, the Renaissance embrasures were replaced on the principal frontage by broad bays with small squares in the style of Trianon. By the first half of the 20th century, the Château had fallen into disrepair, and the northern wing in particular had become a ruin.

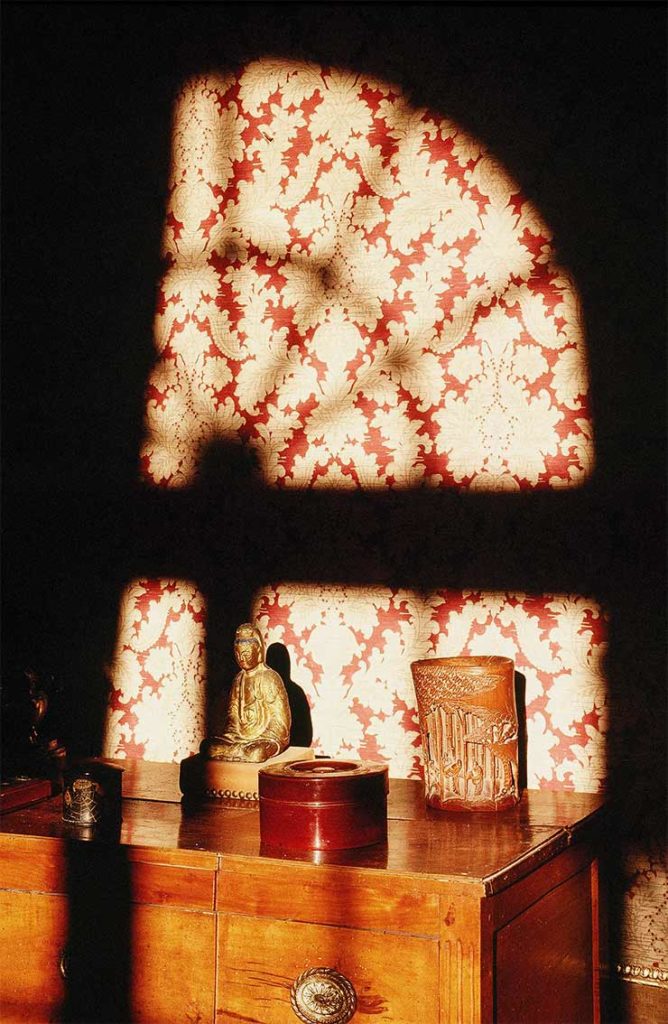

In the 1960s the Ecal family began the immense task of restoring the property and its gardens to their former glory. The result you will see when you visit us: a château with a cachet all of its own in an unchanging rural setting, whose unique light and beautiful vegetation are reminiscent of Tuscany.